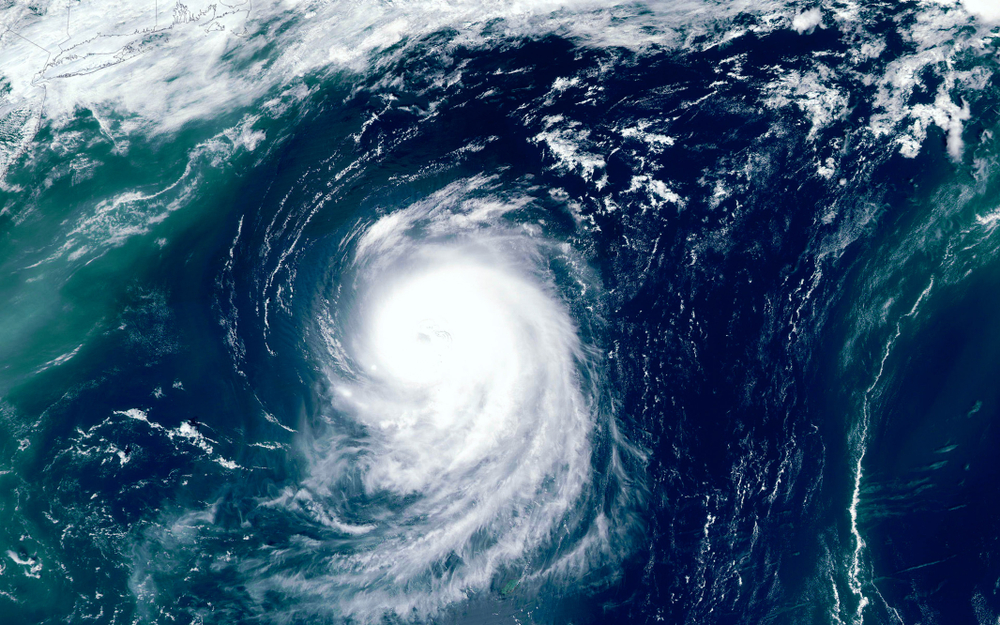

Hurricane season is quickly approaching and this season is expected to be active, maybe even more active than ever.

“Nearly all seasonal projections that have been issued by various agencies, institutions, and private forecasting companies call for this season to be quite busy,” CNN meteorologist Taylor Ward says.

Nearly all of which are predicting an above-average— more than six— this season’s hurricanes will begin on June 1. Some are even expecting a “highly busy” season with more than nine hurricanes.

There are many published forecasts. And while the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s official forecast does not come until May 21, a strong industry-wide consensus in the forecasts suggests the US is in for a productive season.

“In general, the consensus between seasonal hurricane forecasts this year is greater than it has been the past few years,” says Phil Klotzbach, research scientist in the Department of Atmospheric Science at Colorado State University

Those early forecasts usually differ a little bit more.

The average forecast this year— with all 13 groups applying to Seasonal Hurricane Predictions— is eight hurricanes and 17 named storms. Six hurricanes and 12 named storms are seen during an average season.

The conditions look ideal for an active season

Many ingredients are considered by forecasters and climate models when producing a seasonal hurricane climate.

One is temperatures at sea level (SST).

“Sea surface temperatures across much of the Atlantic are running well above normal and have been for the past few months,” Ward says.

Temperatures on the surface of the sea are among the ingredients needed to fuel hurricanes. The warmer the ocean, the greater the fuel available for the storms to tap into.

“The current Atlantic sea surface temperature setup is consistent with active Atlantic hurricane seasons,” says Klotzbach. “With the notable exception of the far North Atlantic, which remains somewhat cooler than normal.”

“Since tropical systems feed off of warm sea surface temperatures, this could certainly lead to a more active 2020 Atlantic hurricane season,” Ward says.

Another consideration is El Niño.

“There is high confidence that El Niño will not inhibit hurricane activity this year,” Klotzbach says.

When El Niño is present it reduces the activity of Atlantic hurricanes due to increased vertical wind shear— changes in wind speed and direction with a height that prevents the development of hurricanes. Normal temperatures or even La Niña conditions create a more suitable environment for the creation of tropical storms.

Most forecast models point to stable conditions or even La Niña conditions during the storm. NOAA says it is about a 60 percent chance that the El Niño Southern Oscillation is favored to stay neutral during the summer. They say the outcome will most likely stay through autumn.

However, this fall forecast for El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) will be revised the day they announce their Hurricane forecast.

The outlier

However, there’s one organization that’s a little bit outlier. An average to a slightly above-normal season is predicted by the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts, or ECMWF. An over-average of named storms this season was expected by everyone else.

According to Klotzbach, the ECMWF seasonal hurricane forecast is built from a variety of vortices that the model spun up during the hurricane season.

“Different numerical models often agree on the overall situation, but differ in details of what they predict for drivers of hurricane variability,” says Tim Stockdale, a principal scientist at ECMWF.

Each of the forecasting groups develops its forecasts using specific techniques.

One computer model, named NCEP, shows a fast development of La Niña, and also very warm sea surface temperatures in the Mexican Gulf. Anyone who uses this model in their forecast would probably predict a higher number of storms.

“The ECMWF model has weaker La Niña development, and sea surface temperature anomalies in the Atlantic are weaker, so both of these factors might give the ECMWF model a less-strong hurricane season than forecasts using NCEP inputs,” Stockdale says, referring to the National Centers for Environmental Prediction.

He also states that their calibration is based on 1993-2015, and does not take into account the more recent last four years (2016-19).

The ECMWF has forecast fewer hurricanes ahead of the season than had been reported in the same years.

One of the challenges this year, Stockdale says, is global sea surface temperatures. There are lots of unusual anomalies and the way they play together is uncertain. The current forecast computer model will incorporate such phenomena in a way that previous models can’t.

“On the other hand, the models still suffer from various tropical biases that mean we cannot be certain that their calculated responses will be correct,” Stockdale says.

For decades, these forecast groups have created hurricane prediction

And though these forecasts aren’t the official NOAA term, they aren’t anything to pass off. Some of them released warnings of hurricanes long before NOAA. Additionally, Colorado State University has been doing seasonal projections the longest of any group.

“CSU started their seasonal hurricane forecasts in 1984,” says Klotzbach. Of the groups submitting their outlooks to the Seasonal Hurricane Predictions website, the one with the longest track record of forecasts besides CSU is WeatherWorks, which started issuing predictions in 1992.

In 1996 the Cuban Met Service began providing seasonal forecasts. NOAA ‘s seasonal forecasts didn’t start until 1998. Other than the Tropical Storm Risk which also began in 1998, in 2000 or later all other groups started their outlooks.

Those forecasts are likely to be wrong

For instance, if the tropical Pacific was warmer and the tropical Atlantic was colder than anticipated, hurricanes would probably be less than expected. Additionally, if a robust La Niña develops and the tropical Atlantic remains warmer than usual, the season could be even more active than those predictions suggest.

“The best recent example of an extremely active season with no US hurricane landfalls is 2010,” Klotzbach says. “That year, we had 12 hurricanes in the Atlantic basin and 0 US hurricane landfalls.”

Climatologically, about 30 percent of all hurricanes in the Atlantic make landfall in the US, he says. But there are around 1 in 70 chances of making 12 hurricanes and 0 US landfall.

“We always say that it only takes one big hurricane landfall to be a bad season,” says Ward. “So all coastal residents should certainly be paying close attention and have their hurricane plan ready for the upcoming season.”