As the virus behind COVID-19 traveled across the globe starting from China, it produced small mutations that accumulated into distinct versions of the virus. By peering into the viral genome, scientists are now sure to observe these versions separately.

For example, here in the US, there is the “West Coast” version of the virus that came straight from Asia and a slightly different version of the “East Coast” that spread through Europe.

Is there a chance to have a safe coronavirus vaccine by New Year’s Eve? Can one version of coronavirus be more dangerous than the other? And should we worry about those new mutations?

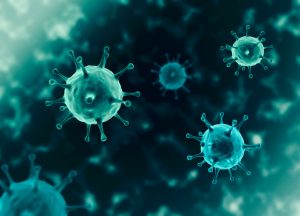

According to virologists, the short response is no. Viruses often replicate themselves, and some of those copies will also have mistakes or mutations. Such mutations are neither good nor bad, and are normal.

So far, the new coronavirus responsible for the global pandemic is normally mutating as virologists would expect to see based on their experience with other related viruses.

“Viruses mutate,” said Dr. Nels Elde, Ph.D., associate professor of human genetics at the University of Utah. “That’s one of the things that makes them such a successful entity.”

“The word ‘mutation’ to people means something bad because it’s got that connotation to it,” said Dr. Vincent Racaniello, Ph.D., Higgins professor of microbiology and immunology at Mt. Sinai School of Medicine of CUNY.

“It simply means a change in the genome sequence. It doesn’t mean that it’s necessarily bad for you at all,” Racaniello said. “Plants grow in the spring. Viruses mutate. It’s no big deal.”

But as scientists across the globe discover more about these mutations, many were able to use these findings to discern whether the virus is getting more or less dangerous. For instance, a group of scientists in China identified two different types of the virus, the L-type and the S-type, in early March.

The L-type was found to be more common, leading to early theories that the virus had developed into a version of itself which is more contagious.

More recently, similar research from the not peer-reviewed Los Alamos National Laboratory in the United States identified a specific mutation in the virus that started spreading in Europe in early February.

The scientists believed this mutation may have helped spread the virus quicker and further because it is potentially more contagious, creating breathless news reports about a deadly “mutant” virus.

However, another group of Arizona State University scientists arrived at a rather opposite interpretation of the mutations they identified. Their research led them to believe that the virus, just like the 2003 SARS outbreak, could become weaker and die off.

Until now, the hypothesis about the infectiousness of the virus are only speculations, Racaniello said. He said there is no iron-clad proof that any strain of the virus has become more infectious, deadlier, or more resistant to potential therapies.

That’s actually good news for humans, as it means that the vaccines and treatments being studied right now will definitely work against all known versions of the virus.

Scientists are closely monitoring the virus to see whether it develops potentially dangerous mutations— or even whether it evolves radically into a new ‘strain’— a term that has a very specific meaning for virologists but has often been used colloquially to characterize the various versions of the virus that exist so far.

A new strain will signify a dramatic event, meaning that the virus is “functionally different” from its predecessor, Elde said. Virologists usually believe, according to Elde, that there is only one “strain” of the novel coronavirus, while in various parts of the world there are many versions of the virus.

What scientists actually observe, in terms of the variations between these viruses, is a phenomenon called viral “isolates,” Racaniello said. That is when the genetic material produces small variations which are not significant enough to make the virus behave in a completely different way.

“You can have different isolates from a single patient, by taking different samples from the respiratory tract and in the lung, for example,” said Racaniello. “It does not mean the differences have any significance whatsoever.”

“I think the bottom line is we don’t really know right now whether mutation signals good news or bad news. It is somewhere in between,” said Dr. Jay Bhatt, former medical chief at the American Hospital Association and an ABC News contributor.

“I think we will understand this better in the coming months.”