Baby Fae

Nowadays, over 7,000 people die every year in the United States of America, because there are not enough organ donors to save their lives. A big part of them usually need a kidney transplant and the only hope is other people’s deaths: a fatal accident resulting in the death of someone whose organs can be taken.

Because of that, surgeons started to look at other living organisms to get the organs they need. Monkeys were the first animals they thought of because they are the most like humans.

Baby Fae, a young girl who received a baboon heart in 1984, died 20 days later after her immune system attacked it. The short life and quick death of the child drew worldwide attention, and many people dismissed the thought of sacrificing our closest animal cousins in order to save ourselves.

The operation was defined as “medical adventurism” in a Washington Post editorial post by a cardiologist. “Baby Fae: A Beastly Business,” read another article in the Journal of Medical Ethics.

However, even though there were many discussions and critics after the transplant of Baby Fae, scientists didn’t give up. In the 1990s, biotech companies and researchers found another animal that might serve as a donor.

Since people eat a lot of pork meat (Americans, for example, eat over 100 million pigs every year), they thought that taking pigs’ organs won’t feel immoral.

If we speak from a scientific point of view, their organs are approximately the same size and have similar anatomy compared to people’s organs. In addition to that, little pigs grow into adults in six months, which is a lot faster than primates.

However, there are some problems with this idea, such as the fact that pigs carry some viruses that can jump to humans. Furthermore, when tried with monkeys, the transplanted organs did not last long because of the rudimentary genetic engineering accessible at the time. Long story short, they were simply too foreign in terms of genetics.

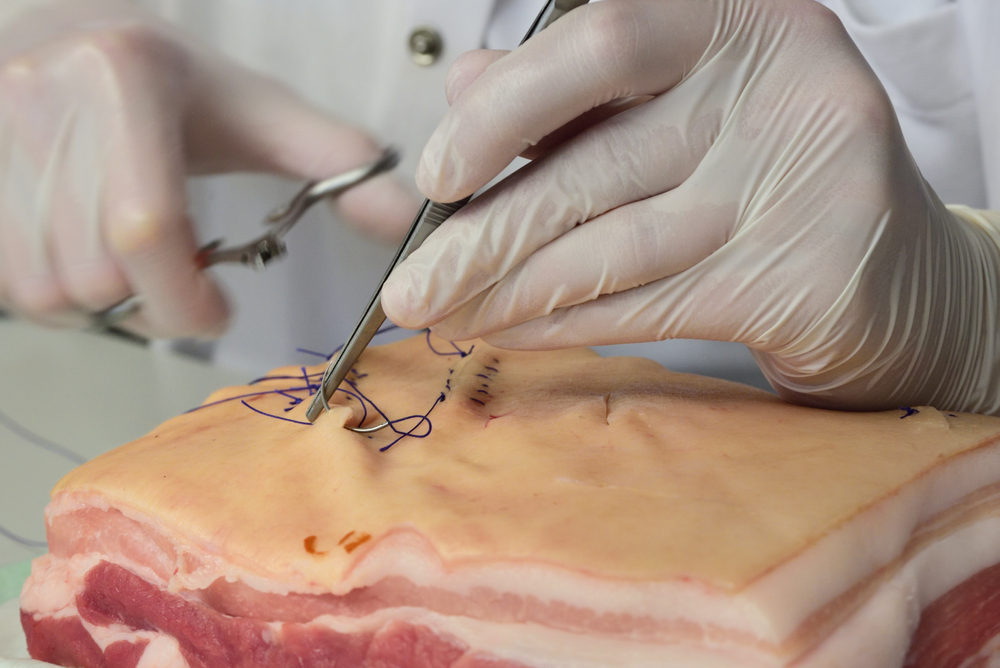

After more than 20 years, advances in genetic engineering have resurrected the possibility of what is called xenotransplant. The biggest question is how many modifications scientists have to do in order to break the species barrier.

eGenesis, a well-funded US corporation that heads the more-is-better group, claims to have made “double-digit” changes to the pigs it raises alongside a Chinese sister company.

Three genes

The pigs from the Munich facility have three important genetic modifications, which were made over 10 years ago. All of these changes were created in order to prevent humans and baboons from rejecting their organs.

There is a gene that produces galactosyltransferase, which is a sugar responsible for making the recipient’s immune system reject an organ from another species.

The second change researchers made was to add a gene expressing human CD46. This is a protein that aids the immune system in attacking foreign invaders without overreacting and causing autoimmune disease. The third and the last change added a gene for thrombomodulin, a protein that prevents blood clots from destroying the transplanted organ.

According to Eckhard Wolf, the director of the Center for Innovative Medical Models on the periphery of Munich, a smaller number of modifications can be better regulated and measured, and their consequences are easier to demonstrate.

If something goes wrong, which is often with xenotransplantation, it will be obvious what the problem is. With more changes, there are more potential issues. “At some point, you’re in a scenario where you don’t know what another genetic alteration accomplishes,” he says.

1 thought on “Pig Organs That Can Save Humans’ Lives”

I had the pleasure of meeting some people back in January of 2018 and one of them was a man in his 50’s or so who originally came from Peru. His girlfriend and I were talking one day and she tells me about how have cancer and beating it opened her up to a whole new world. Then I asked how the two of them met and where he was from so she begins telling me the story and how a few years back she had thought she was going to lose him due to a bad heart and the organ donor waiting list here in the United States being so long. Then she proceeds in telling me that they ended up going to Peru for him to have a heart transplant. This heart he had transplanted in him was from a pig and of course America wouldn’t do that type of surgery for one: because of the nature of it and two: because it would cost a fortune. I found this article interesting because, Peru has already been doing this with what seems to be very successful rates and no huge price to save someone’s life. Maybe, the above mentioned groups could get ahold of the Peruvian People and get more insight to all of this. One thing I know is that the older gentleman with the pig implanted heart was in great shape and out working men half his age.