The media is full of scientific articles and research with claims of breakthrough studies performed on animals. However, are animals that similar to us, humans, in order to make relevant health discoveries? Can animals ever faithfully model human health?

Devoted readers of medical and science news are probably familiar with animal testing predominating in biomedical research. From cancer to nutrition and studies on metabolism, animal testing is now very often identified in articles, as well as by scientists and journalists drawing parallels between animals and humans.

Nonetheless, problems can come to light when researchers make a prognosis about human health based on animal studies. In scientific terms, this concept is called clinical relevance. Many biomedical subventions and grant funding organizations require a justification based on the use of animal models by anticipating how likely their findings will be relevant to human health.

For the time being, journalists use catchy news headlines to bring attention to their articles, sometimes omitting the relevance of how clinically applicable that study really is. Sometimes it can get even worse, they omit writing the fact that the scientists performed their study on animals, not humans, leaving out some important information.

Can we be sure that conducting animal testing and studies will be relevant to human health, and who is to blame when an article includes sweeping statements about clinical relevance?

Between mice and humans, it is important to find out how animal studies have contributed to biomedical advances, and why some researchers sustain that animal testing models harbor no clinical relevance.

Animal models date back to ‘2000 BC’

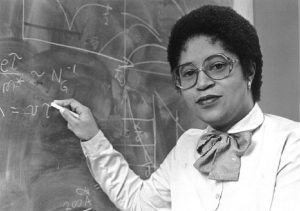

“Before we delve into the early days of animal studies, I am going to add in a disclaimer. During my time as a research scientist, before joining Medical News Today, I was involved in several studies that used a large pig model of wound healing. Although I have made every effort to approach this topic factually, I cannot guarantee that my experiences have not left me without some level of bias,” said Dr. Vootele Voikar from the University of Helsinki in Finland.

Kirk Maurer, from the Center for Comparative Medicine and Research at Dartmouth College in Lebanon, NH, and Fred Quimby, from Rockefeller University in New Durham, NH, discusses the history of animal models in biomedical research at length in a chapter in the 2015 book Laboratory Animal Medicine.

“The earliest written records of animal experimentation date to 2000 BC when Babylonians and Assyrians documented surgery and medications for humans and animals,” they write.

Even though many centuries may have passed since then, the information is still assumed to be factual today.

Galen’s discovery in the second century AD stated that blood, not air, flows through our arteries, identifying in 2006 four genes that can revert any cell into an embryonic stem cell-like state when activated, animal testing models were the methods that lead to this huge scientific progress in the biosciences.

The scientist couldn’t have done it without animal models, describing the “ideal” animal model: “Perhaps the most important single feature of the model is how closely it resembles the original human condition or process,” they explain.

Nevertheless, any model will only go so far, they admit: “A model serves as a surrogate and is not necessarily identical to the subject being modeled.”

Animal models in modern medicine

Françoise Barré-Sinoussi and Xavier Montagutelli, from the Institut Pasteur in Paris, France, discuss the involvement that the animal studies have made in medicine in a 2015 article in the journal Future Science OA.

“The use of animals is not only based on the vast commonalities in the biology of most mammals, but also on the fact that human diseases often affect other animal species,” they explain.

“It is particularly the case for most infectious diseases but also for very common conditions such as type 1 diabetes, hypertension, allergies, cancer, epilepsy, myopathies, and so on,” they continue.

“Not only are these diseases shared but the mechanisms are often also so similar that 90% of the veterinary drugs used to treat animals are identical or very similar to those used to treat humans.”

Both Maurer and Quimby, as well as Barré-Sinoussi and Montagutelli, cited many Nobel Prize winners and their studies performed on animals, leading to the progress of new treatments relevant to modern medicine.

This includes the work by Frederick G. Banting and John Macleod who isolated insulin from dogs, Emil von Behring and his work on vaccines in guinea pigs and rabbits, and James Allison and Tasuku Honjo’s research in mice and mouse cell lines in the field of cancer immunotherapy, which won them the Nobel Prize in 2018.

Additionally, without any doubt, animal models have made an enormous contribution to modern medicine. That said, Barré-Sinoussi and Montagutelli also add that “it is, however, noticeable that the results obtained on animals are not necessarily confirmed in further human studies.”

However, even if we share a significant proportion of our genetics with some animals used by the scientist in research, there are clear genetic differences.

“While some people use these differences to refute the value of animal models, many including ourselves strongly advocate for further improving our knowledge and understanding of these differences and for taking them into account in experimental designs and interpretation of observations,” they explain.

Questioning clinical relevance

However, not all scientists have the same opinion as Barré-Sinoussi and Montagutelli.

In a 2018 paper in the Journal of Translational Medicine, Pandora Pound, from the Safer Medicines Trust in the United Kingdom, and Merel Ritskes-Hoitinga, from Radboud University

Medical Center in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, argues that “preclinical animal models can never be fully valid due to the uncertainties introduced by species differences.”

The article focuses on the pharmaceutical industry, which requires animal studies at the stage before a drug enters clinical trials. If these preclinical models aren’t made, then it is not possible to test new drugs in humans.

“While many factors contribute to the poor rates of translation from bench to bedside (including flawed clinical trials), a predominant reason is generally held to be the failure of preclinical animal models to predict clinical efficacy and safety,” they write.

Pound and Ritskes-Hoitinga highlight an unsuccessful example from 2006 when despite the fact that preclinical studies had shown the experimental drug TGN1412 to be safe, the participants of the trial did suffer some severe life-threatening reactions.

And there are the scientists who see the value of performing testing on animals, but advises caution when choosing the right model and interpreting the results.

Dr. Vootele Voikar, from the University of Helsinki in Finland, uses mice in his neurobehavioral research.

When I asked Dr. Voikar how relevant animal models are to human health, he told me that “some of the fundamental rules, when using animals in basic research, [are] to avoid anthropomorphizing and to take species-specific differences into account as much as possible.”

“With careful design of the experiments, understanding the validity issues at different levels, and appropriate critical interpretation of the results, the relevance, and some confidence can be achieved.” -Dr. Vootele Voikar

Dr. Voikar also addresses his thoughts about the journalists often misinterpreting or mispresenting what scientists publish.

“I think the main problem is with scientists and their press releases — how they sell the data and results, how strong the evidence is they find in relation to some devastating disease, promises that are not yet there, although based on their interesting and important but often preliminary findings,” he explained.

“Usually it means that more research needs to be done, to find out if the findings are reproducible and applicable to the other conditions. The care or treatment does not become available overnight, unfortunately, in the majority of cases. However, (over)selling is often needed for attracting new grants for the research” he adds.

He advocates “multidisciplinarity dialogue between the clinic and basic, preclinical work — too often the biologists studying disease models have very limited knowledge of the respective clinical condition and spectrum for differential diagnosis.”

“To be critical, avoid hype, ask and present different views to promote objective discussion, and consider applicability and generalization of the findings — for that specialized science writers are needed.”